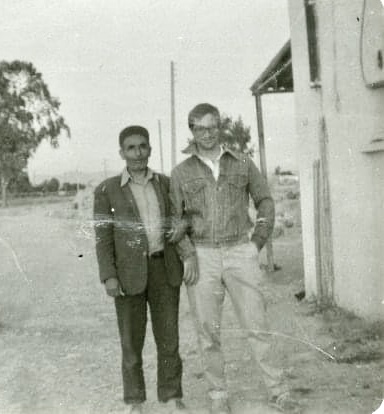

[Karl Stark was a Peace Corps volunteer in Tunisia from 1980 - 1982.]

At dusk, the setting sun, so brutal at noon, paints desert sky in pastel hues and the inky silhouettes of the eucalyptus standing in a ragged line following the course of the railroad tracks are blurred, indistinct like a watercolor blotted by some divine hand. Light spills out of Café Pahr and lingers in a haze of cigarette smoke illuminated by yellow light from the bare incandescent bulbs which line the ceiling and the flickering blue/white light from the single small black and white television mounted on a table opposite the open door - from what I can see, it appears to be playing an Egyptian telenovela, but nobody pays it any mind. Farm hands, shepherds and local merchants are seated around each of the six plastic tables playing a kinetic card game where the player with the winning hand slaps his cards on the table and shouts “Scooba!!!”, much to the consternation of his opponents. Arguments erupt as tempers flare but, like a thunder clap from a midsummer storm, they dissipate rapidly and the game resumes.

A monochromatic poster of Mohammad Ali vs. George Foreman is taped to the whitewashed cinder block wall behind the television, bordered by one of James Brown holding a microphone stand and another of an Egyptian actor in a boxing pose.

Handsome Tahaar arrives on his Motobecane Moped, adjusts the smart French Foreign Legion cap he purchased at the souk last Saturday, flashes me a toothy grin, waves and enters the café to be greeted by a chorus of “salam”.

Slubba, the old man wearing baggy trousers over brown plastic sandals, passes me riding his donkey, his mandella - straw hat - bobbing in rhythm to the beast’s uneven gait. His hands are like gnarled roots, his grin entirely toothless and he gives me a nod.

“Monsieur Karlo.” he says with a slight nod of his head.

As he passes, I imagine I hear the muffled clink of bottle hitting bottle from the satchel around the donkey’s neck.

Yellow light also spills from the open doorway of Lauouni’s general store next to the cafe where the corpulent Hassan Lauouni rests his elbows on the counter and waits for his next customer. He stands as I enter and greets me with a smile.

“Salam alaik ya Monsieur Karlo. Snuua Hualiak?”

“Salam alaik ya Monsieur Karlo. Snuua Hualiak?”

“I am fine” I reply in Arabic.

“And your family?”

“They are all good, too”

“What can I get for you? Would you like a can of green peas?”

When Mr. Lououni laughs, his eyes are small and dark like two raisins in the center of an unbaked loaf of khubz tabouna and his belly quivers underneath his blue djellaba.

“Why, yes. Please fetch me a can of your finest green peas,” I reply with a flourish…then I laugh. “And a bottle of whiskey”. When I first arrived in Chaouat, my Arabic vocabulary was minimal but I knew how to say “eggs” and “green peas” so I spent several weeks eating just those two consumables and the villagers concluded that peas and eggs must be staples of the American diet.

“Tsk, tsk, tsk,” he clucks. “You KNOW I do not have whiskey.”

We laugh together.

Like the café, the store is a one room edifice constructed of cinder blocks and white washed. Signs advertising Coca Cola - in Arabic script - Fanta, Cidre, and Choco-Tom cookies adorn the outside walls on either side of the sky-blue door which, more often than not, is held in the open position by a rock. From behind the service counter, one can easily view the entire contents of the shop: canned vegetables, the afore-mentioned sodas, cookies, bread, eggs and dairy as well as hand tools, various pharmaceuticals, pencils, paper, Les Temps de Tunis newspaper (both the French and Arabic versions), thong sandals, sunglasses…but no alcohol. Between Mr. Lououni and me is an understanding that, in the Islamic faith, the consumption of alcohol is haram, forbidden so my request for whiskey is all in jest.

A pair of barefoot boys enter the shop.

“Monsieur,” the taller of the two addresses me. “Avez vous de monie pour des bon-bon?”

“Bar imshi” growls the shopkeeper. Get OUT!

The boys beat a hasty retreat.

The shopkeeper frowns as he watches the boys exit but his smile returns as his eyes meet mine and our conversation resumes.

“So, what can I REALLY get for you?”

“Let’s see…I need a liter of milk, a cup of yogurt, a loaf of French bread, half-a-kilo of hummus, three eggs and some writing paper.” I hand him my shopping basket. It’s a soft sided straw basket with woven loop handles just like the one which Mother would fill with oranges, sliced egg sandwiches, towels and lotion before setting out to Wellfleet with us in the Biscayne for a lazy afternoon passed lying on the towels in the scant shade of an umbrella, our eyes heavy from the hypnotic roll of the waves and the sun and the cry of the gulls.

“Very good,” he replies, turning and shuffling down the aisle. I assume he’s wearing sandals but his djellaba nearly reaches the floor so I can’t see his feet.

After a few minutes, he places the basket on the counter and I open it to make sure nothing was forgotten. The eggs are wrapped in newspaper, the hummus is in a cone fashioned from heavy paper and the box of Parmalat milk is on the bottom of the basket. Both the milk and yogurt are irradiated because the shop doesn’t have a refrigerator and the ambient heat would quickly spoil any dairy product.

“Look okay?” he asks.

“Yes. What do I owe you?”

“Four dinar and a half.” He answers without hesitation and I suspect the sum may be a bit high but I’m tired and not in the mood to haggle so I drop several coins into his soft palm. I close the basket and turn to leave.

“This is not like America,” he says. "In America you have supermarkets…I see them on television. And everyone is rich. Am I right?”

“No, Hajj Lououni. I am from a small village like Chaouat and we do not have a supermarket but we DO have a hanut…a small store just like your’s”.

He looks astonished.

“Really??” What is the name of the store?”

“Massino’s General Store.”

“Mah..sin..ohz gen..rl tor…” he repeats, stumbling over the unfamiliar English consonants.

“But everyone calls it “Aggies…that’s the name of the owner.”

“So, Monsieur Auggie…is he a good man? Is he honest?”

“Aggie isn’t a man at all. Aggie is a woman!”

“Buh, buh, buh…A woman owning a store…” he shakes his head, his mouth drawn into a tight line."I bet the men who come in are interested in more than just groceries," he says, raising his eyebrows and cocking his head. "Does this Auggie have a husband?"

"Yes, he works for HER...but it's not what you think."

I smile, conjuring up an image of Aggie, her silver hair drawn back in a tight bun, matronly in her daisy print dress, sensible shoes and change apron, giving the death stare over her pince nez glasses to the schoolboys acting furtively at the candy counter. "I'm watching you and I know your daddies!" she'd holler, causing them to scatter.

"Aggie is a jida, a grandmother," I explain. "But, in America, women shop for food more often than men so she is not the only woman in the shop at any time."

Mr. Lououni hesitates, digesting this information, then replies "That's just not right...I mean, I know life is different in your country but...women in the hanut....that's just not right."

"Yes, life is different in America," I agree. I turn toward the door just as Monir and Habib enter. "Salaam," I greet them with a nod, bringing my right hand to my chest. "Tusbih ealaa khayr, ya Hajj Lououni" Good night, Mr. Lououni.

It is fully dark when I bid farewell to Mr. Lououni and exited his shop. Turning right, I walk the length of Avenue Habib Borguiba toward a group of men gathered around a rough-hewn table set between two eucalyptus and illuminated from above by a string of bare light bulbs strung between the trees. Upon the table are piled a variety of fruits and vegetables.

It is fully dark when I bid farewell to Mr. Lououni and exited his shop. Turning right, I walk the length of Avenue Habib Borguiba toward a group of men gathered around a rough-hewn table set between two eucalyptus and illuminated from above by a string of bare light bulbs strung between the trees. Upon the table are piled a variety of fruits and vegetables.

“Aslamma alikum,” I greet them.

“Salaam alik” they reply in unison.

Behind the table, Hashmi, the greengrocer, a man my father’s age, or perhaps a bit older, is seated on an overturned milk bucket. He is wearing a cream-white djebella robe and a chechia, the traditional red skull cap and, in spite of his humble seat, he sits erect, his arms akimbo in a posture of inscrutable dignity yet the eyes in his wizened brown face are gentle, benevolent. He is flanked by his three sons, Mohammad, Hassan and Mohsen, who remain standing.

“Aslamma, ya sabi” he greets me. “Hello, friend.”

“Aslamma, ya bubba” I reply, respectfully, bowing slightly and covering my heart with my right hand as though I were addressing a priest.. “Hello, father.”

“What may I get you?” he asks.

“I would like two artichokes and…”

“Artichokes??” Mr. Hashmi interrupts. “You do not want artichokes. That is charity food…for the poor.”

“But you sell them…”

“Yes,” he explains. “The poor people gather them on the hill as they graze their sheep and I give them a few millimes for a basketful but only the poor people eat them. You do not want to eat artichokes.”

“But, in America, wealthy people pay real money…dinars…for artichokes!” I exclaim. “How much for two?”

“Bah,” he replies, dismissively. “Just take them."

“Thank you. Then, how about a rotl of beans, one pomegranate and two quince”

Mr. Hashmi fetches my order from the collection of fruit crates under the table. The golden quince are mottled with dark spots, an indication that they weren’t treated for worms. DDT is still legal here. I will eat around the dark spots.

“That’s two dinar and 100 millimes.”

I place two notes and a coin into his weathered palm and he nods a thank you.

“You know,” the grocer says, “I worked for the Americans during the big war. They were fighting the Germans over in Kasserine.”

“Really? My father fought in the war too. He was a soldier, too.”

“Oh, I wasn’t a soldier,” Mr. Hashmi explains. “I worked in the food store. And I remember how to speak American!” “TWO PLUM FIFTY CENTS” he shouts in English.

“What does that mean?” asks Hassan and I translate, much to the old man’s satisfaction.

“SONOFABITCHDAMNITALL” Mr. Hashmi continues. “What does that mean?” he asks eagerly. I hesitate, looking from Mohammad to Hassan to Mohsen who appear quite intrigued. Mr. Hashmi is a proud, self educated man who reads the Koran in the mosque and, in the many months I’ve known him, I have never heard him curse…except for now.

“Oh, there is no translation,” I lie. There is actually a direct translation. “It’s just an expression. No meaning.”

“C’mon,” Hassan demands. ”What does it REALLY mean??”

I sigh.

“It’s a curse word,” I reply.

The two younger brothers burst into laughter, much to the chagrin of Mohammad and his father.

“Salam alaik ya Monsieur Karlo. Snuua Hualiak?”

“Salam alaik ya Monsieur Karlo. Snuua Hualiak?”

It is fully dark when I bid farewell to Mr. Lououni and exited his shop. Turning right, I walk the length of Avenue Habib Borguiba toward a group of men gathered around a rough-hewn table set between two eucalyptus and illuminated from above by a string of bare light bulbs strung between the trees. Upon the table are piled a variety of fruits and vegetables.

It is fully dark when I bid farewell to Mr. Lououni and exited his shop. Turning right, I walk the length of Avenue Habib Borguiba toward a group of men gathered around a rough-hewn table set between two eucalyptus and illuminated from above by a string of bare light bulbs strung between the trees. Upon the table are piled a variety of fruits and vegetables.